June 11, 1998 |

|

Popular device tested on $14,000 Yorick

Cell phone's electromagnetic field comes under scrutiny

by Sylvain Comeau

In the wake of nagging fears about cellular phones and claims by some users that the devices may cause cancer, two Concordia professors of electrical engineering were recruited four years ago to help determine just what happens when someone holds one of the ubiquitous devices up to his or her head.

Stanley J. Kubina and Christopher Trueman, working in Engineering's EMC (Electromagnetic Compatibility) lab, started by developing a computer model for calculating the energy deposited in the head and hand from cellular phones.

They are conducting the study for the Communications Research Centre in Ottawa, part of Industry Canada. The project is a small part of a larger program with Health and Welfare Canada aimed at attempting to predict the electromagnetic fields (EMF) emitted by a variety of portable transmitters.

"Our mandate with this project is to develop a modelling and measurement methodology that will allow [our sponsors] to determine what these external fields are," Kubina said.

Kubina and Trueman are not directly addressing the issue of the safety of cellular phones, although their work has confirmed what the biomedical community had already determined: that the devices emit EMFs that are well within the levels considered safe.

"We are not primarily concerned with safety issues, but they spring directly from our results," Kubina said. "That's because once you have the ability to predict external fields, you can [also] predict them internally, inside the head, brain, hands and so on.

"The safety criteria, so far, are based on the thermal heating properties of the electromagnetic fields. Cell phones are within safe levels, but some people are still investigating long-term effects, such as the susceptibility to cancer from long-term exposure [to EMFs]."

Their work will be used to test existing cell phones and other devices, or determine the safety of new products before they come to market.

"There will always be a need to test handsets for compliance with regulations concerning field strengths inside the head," Trueman said. "One way to do that is by computation. No manufacturer will make a handset with an antenna which, in the simulation, violates a regulation."

Computer simulations to test hand-held devices have been used before, but the simulations themselves have not undergone much scrutiny.

"The methods we are using are state-of-the-art," Trueman said, "but how good are they? They are approximations. So our main concern was validation of these computer models. We found that the agreement [between the computer models and the measurements] was very good. We were pleasantly surprised."

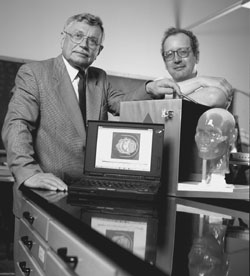

They confirmed the accuracy of their computer projections through tests on Yorick, a plastic representation of a human head and hand, filled with fluid meant to simulate the human brain. Yorick is named after the skull which Hamlet addresses in the Shakespeare play. Alas, poor Yorick may soon be put out to pasture, Kubina said.

"Eventually, the final step will be to do measurements on a person holding a cell phone, and we will examine his brain with an MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scan. We started with the computer model and Yorick because we needed to verify our methodology with a model we could control."

Stanley Kubina and Chris Trueman with Yorick, the model head used to test interference for cellular phones.Peter Seraganian and Thomas Brown