Floating the yuan won’t solve US deficit: Economist

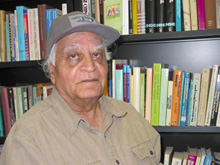

Jaleel Ahmad

Photo by Karla Amirault

Economics professor Jaleel Ahmad says the U.S. government has been leaning on the Chinese to float the yuan in the expectation it will revalue upward.

China has been a longtime passion for Ahmad, who has taught at the University of Shanghai and has advised the Chinese ministry of finance on the reform of the exchange rate.

“American Treasury Secretary James Snow has made a number of trips to China to try to persuade them,” Ahmad said in an interview. “The feeling is that if the Chinese do this, the American trade deficit would diminish, but this is an incorrect assessment of the situation.”

Last August, the U.S. trade deficit with China climbed to a record $18.1 billion, almost one third of the total U.S. trade deficit for the month. It was probably fuelled by a surge in demand well ahead of the holiday shopping season.

As Ahmad sees it, there are three hurdles facing proponents of a floating yuan.

One is the near-impossibility of determining what the rate should be. Indefinite floating without a benchmark does not appeal to the Chinese. The yuan was pegged in 1994 at about 8.28 to the U.S. dollar (about 6.62 to the Canadian dollar). Today, it is estimated to be undervalued by between 10 and 50 per cent.

A second problem is that a revalued yuan would make ongoing negotiations to establish a China-Japan-South Korea economic union even more arduous.

The third difficulty, one that Ahmad believes he alone has identified, goes to the root of the “where’s China going?” debate recently featured in a week-long series in the National Post.

He says China has a dual export economy. There is the one that foreign investors have built over the past decade in the form of a modern, large-scale export sector, which has seen a soaring increase of 25 per cent annually. Then there is the much more modest economy of domestic producers, which has grown by only 5 per cent a year.

Ahmad says the yuan is probably undervalued for the highly productive “new” economic sector, but revaluing it upwards would have a devastating effect on indigenous Chinese firms, mostly state-owned, over-staffed, inefficient and buffeted by trade liberalization following the country’s recent entry into the World Trade Organization.

“Very slowly, the Chinese authorities are trying to solve that, but they feel it’s not the opportune time to revalue the currency.

“The other problem is more technical. If they revalue, China will lose some cost advantage. In order to regain that advantage, they could lower wages. Chinese labour costs are already quite low, so that would not help the workers.”

The issue has some relevance to the U.S. election debate about job outsourcing, but it does not play a major role for Canadians.

“If revaluation does take place, perhaps imports from China will fall, but Canadian exports are mostly natural resources and timber, and they are governed by other economic parameters than changes in exchange rates here and there.”

Ahmed cautions Canadians concerned about American economic performance that solutions will not come easily. The root of the problem is the U.S. deficit.

“With their trade imbalance, Americans are, in effect, borrowing from China, Canada and almost every country in the world.

” Born in India, educated in the Netherlands and the United States, Ahmad taught at MIT and Harvard and, for 33 years, at Concordia.