Expo 67 was our window into the future

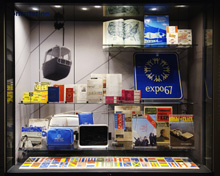

One of the vitrines of Expo 67 materials at the Canadian Centre for Architecture.

Photo by Andrew Mitchell

A “utopian faith in the future” was what marked the era of Expo 67 in Montreal, according to the curators of a show at the Canadian Centre for Architecture.

Rhona Richman Kenneally (Design and Computation Art) and Johanne Sloan (Art History) were invited by the CCA to shine the spotlight on an event that still brings dreamy looks to the faces of Montrealers over 40.

Not Just a Souvenir is the name of their exhibit, which is on at the CCA all summer. It complements the CCA exhibition The Sixties: Montreal Thinks Big.

The two scholars also organized a colloquium in early April, Montreal at Street Level, that brought together local and international scholars from various disciplines to look at how Montreal's cultural identity was transformed in the process.

Expo 67, a world’s fair held on Montreal’s Ile Notre Dame and Ile Ste. Hélène the summer of 1967, brought together architecture, art, design and technology, encouraging its 50 million visitors to enter a world of delightful fantasy.

The potential of the future and the role of technology were perceived as endless. From a prototype of an IMAX theatre to chickens raised in battery farms, Expo 67 exemplified the idea that “humans can do anything if they put their minds to it.”

With designer Jennifer de Freitas, Richman Kenneally and Sloan created four hall display cases, or vitrines. Each contains memorabilia arranged thematically to show “a dynamic tension between modernist impulses and articulations of tradition, folklore and history.”

Visitors were helped to make the transition from the real world to the imaginary one of Expo. Upon arrival, these tourists became “citizens,” and were issued “passports” that were stamped with each visit to a new “country,” or pavilion. Magazines fell in with this approach, and used it in their presentations of Montreal as a destination for tourists.

The images on Expo postcards typically were illustrated paintings or photos of maquettes of the pavilions. People saved the postcards to recall the pavilions, and often remembered the illustrations rather than the real thing.

Expo hostesses wore uniforms not unlike Captain Kirk’s crew on the Star Trek Enterprise. Knowledgeable and helpful, they represented the past, present and future, helping visitors understand what they experienced.

Pavilion restaurants featured menus where everyday foods from many countries were culturally re-interpreted, often more akin to fantasy than reality. In the Canadian pavilion, diners were seated on sealskin-covered chairs and served by a waiting staff attired in buckskin.

Much of the Expo paraphernalia left the site and was incorporated into daily life: umbrellas, perfume, recipes, a Daredevil comic book with the Expo site in the storyline, beer bottles and place mats.

Expo was an opportunity for Canada to prove to the world it was capable of hosting such a prestigious event, and an opportunity for other countries, such as Russia, Cuba, China, to present their doctrines and cultures in a world divided by the Cold War in an age defined by propaganda.

It was also a chance for contemporary designers and architects to define their vision of modernity. A publication of essays that developed from the April colloquium is forthcoming. The Canadian Centre for Architecture is on René-Lévesque Blvd. just east of Guy St., but the entrance is on Baile St.