Irene F. Whittome makes art of stone, water, sky

File Photo

A lecture by Irene F. Whittome is a work of art in itself. She chooses her words carefully and delivers them gravely, almost like a meditation. A rapt audience at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts listened to the longtime Concordia teacher and celebrated multimedia artist describe the latest chapter in her creative evolution.

Whittome has become increasingly preoccupied with place. This includes creating a Japanese interior space in her loft, and buying 35 acres of bush, including an abandoned granite quarry in Ogden, near Stanstead, Quebec.

After three major exhibitions in the late 1990s, she wanted “to stop and be very, very quiet.” Nevertheless, she got an FCAR grant from the Quebec government that involved teamwork, an unusual move for an artist who habitually works alone.

The team, which includes an art historian and an anthropologist, has been working in Stanstead near the Quebec-Vermont border, documenting its past and exploring its potential.

Every summer for the past three years, Whittome has been recording through photography various aspects of life in Stanstead. Granite, which she calls “earth’s memory, in a fashion,” carries special interest for her. Her interpretation of activity in the quarries will be the subject of an exhibition, Conversation Adru, to be given at Bishop’s University in the spring of 2004.

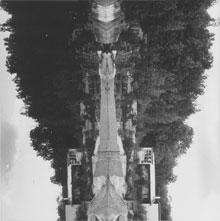

Beverley Junction (2002)

For an abandoned quarry, she said, “There’s a lot going on.” The sound track produced for the Bishop’s exhibition played at intervals during her talk. Surprisingly, there was no birdsong or wind soughing through the trees; instead, it was overhead planes, scraping sounds, the rumble of heavy machinery.

Whittome comes by her attraction to this site honestly; her father was a construction engineer in British Columbia, and she grew up around giant logs and bulldozers.

She took her students to the cutting mills, where the boulders of granite were cut into stone slabs destined for buildings or tombstones. The Ogden quarry had been abandoned when flaws were found in the granite.

She showed slides of photographs taken in the dusty, ambient light of old stone sheds on a nearby property, and the site of the former Butterfield Tool factory, an “empty space full of conversations.” She takes panoramic views of the shoreline, with the industrial landscape perfectly reflected in calm water, then turns them 90 degrees to stand like mysterious totem poles, or Rorschach tests. She has pursued this instinct for tall vertical shapes before, notably the majestic installation Linden/ Tortue for a show at the Can-adian Centre for Architecture in 1998.

Whittome said her teaching is inseparable from her development as an artist, and she continues to be fascinated by what teaching brings to her art. In fact, she would like to develop her quarry as a place to teach and record sound.

Her quiet exploration of this humble place in the woods has taught her the value of attentiveness, of listening to one’s self. “The unconscious knows what it wants,” she said. “It’s all there throughout your life, but some things are closer to the surface.”

Her talk on March 10 at the MMFA was part of a series of three lectures by artists. She was introduced by Dominic Hardy, who co-ordinates the museum’s education program, and is in the midst of a doctorate in art history at Concordia.

Also at the museum this season is a series of lectures by François-Marc Gagnon, director of Concordia’s Gail and Stephen Jarislowsky Institute for Studies in Canadian Art, which starts March 31, and a major show on Jean Cocteau, for which archivist and historian Oksana Dykyj, a former Concordia employee, will give two talks on May 15 and 16. For more, please consult www.mmfa.qc.ca.