Author Alistair MacLeod on the ties that bind us

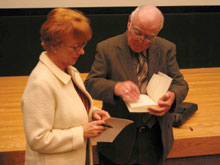

Alistair MacLeod signs No Great Mischief for CTR editor Barbara Black.

Atlantic Canada is suddenly sexy for writers from elsewhere — Anne-Marie MacDonald and E. Annie Proulx have used eastern Canada as the setting for recent bestsellers — but Alistair MacLeod has been writing about Cape Breton for decades.

MacLeod is author of two short story collections and the 2001 International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award winner, No Great Mischief, from which he read excerpts last Tuesday in the English Department’s Writers Read series.

He was raised in Cape Breton in a Scottish environment, an upbringing that percolates through his writing. “I am very strongly influenced by tradition,” he said. “That’s who I am.”

However, his is a tradition that is highly regional. “In a country like Canada,” he said, “it’s hard to say there is a Canadian tradition. The people are not homogenous.”

One of the defining aspects of his upbringing was the vibrant oral tradition in which he was raised. MacLeod still defines himself largely as a storyteller, and several of the audience members later commented on what a pleasure it was to hear MacLeod’s words read aloud.

However, his is a highly refined form of storytelling. Often dubbed the “writer’s writer,” MacLeod is widely acknowledged as one of Canada’s greatest living authors, a title that has been earned by decades of plodding, but exacting, work.

“I always begin with an idea,” he explained, “then invent certain characters to act out the various takes on this idea.” Before writing he will work through all the nuances of the concept he wishes to explore, decide the exact course of the plot and quirks of the characters and, only then, will begin composing, writing from start to finish with little deviation from his original scheme.

No Great Mischief, for example, is an exploration of belief and loyalty. The narrator, Alexander MacDonald, a Cape Breton emigré living in southern Ontario, explores the “invisible lines” of allegiance that tie him to his family and clan. The extended family suffers through tragedies and successes, occasionally split apart but always “look after their own blood,” leading MacDonald to conclude, “All of us are better when we’re loved.”

Though elements of the story seem to correspond with aspects of MacLeod’s own life, he is emphatic that he is not an autobiographical writer. “I think it’s kind of limiting,” he said.

Since the success of his novel, MacLeod’s writing is reaching and touching a wider audience, a fact that pleases him. The lucrative IMPAC award — 100,000 British pounds — was a catalyst for widespread recognition. Since the members of the judging committee were drawn from all countries where English is spoken, it was also a validation of the universality of his writing.

A notoriously slow and careful writer, the recently retired University of Windsor professor was cautious when asked if he had any projects in the works. “I’m thinking,” he said with a smile. “First I think, and then I write.”