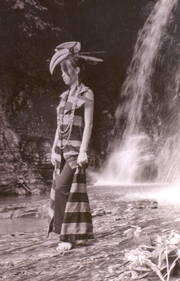

Young women of the Chittagong Hill Tracts model dresses made with textiles

hand-woven in the traditional style.

|

by Barbara Black

Arshi Dewan is an MA student in art education who is already putting her

studies to practical use. She is the convener of Rygula, a project to

revive an ancient weaving industry in the Chittagong Hill Tracts of Bangladesh.

“It is not a commercial business, but it has the potential to evolve

into a small industry in the future,” she said in a recent e-mail

interview. “I am hopeful that it can become a great income-generating

program for the weavers.”

For Dewan, the project was social intervention, part of her academic work

as an artist and textile art historian. “I wanted to do a social

experiment on how the local people perceived their own dress in relation

to culture and identity.”

Cultural identity in a modern

world

The people of the region have a rich textile tradition, but this is in

danger of giving way to cheap modern clothing. Rygula’s explanatory

brochure says, “With this collection, we hope to renew people’s

interest in asserting their cultural identity through dress, and to inspire

them to wear indigenous woven clothes in the public sphere.”

The project buys hand-woven textiles to encourage the existing weavers

in the community, and also enables young people to learn these skills.

About 20 selected weavers participated in the project, women renowned

for the quality of their work. The experienced weavers are paid according

to the size and complexity of the order, and the younger weavers are encouraged

to experiment with new designs.

Dewan concentrated on the women of Rangapani village, who, like her, are

Chakma, one of the 11 peoples of the Chittagong Hill Tracts.

“They live close to each other, but there is no central place to

meet, so it is not like a factory. They work around their own schedules

and household responsibilities,” Dewan explained.

“Unfortunately, not many local women in the town wear the traditional

dress anymore. Since Bangladesh is a conservative society, the other ethnic

groups do not feel free to be themselves. The status of indigenous dress

has declined over the years, and the women wear the Bengali dress (selwar

kameez and saris).”

For Dewan, this is an opportunity to give something back to her own people.

“I feel a strong sense of belonging, and I have a responsibility

to restore the dying art of weaving and bring out the creative aspects

of my culture.

“My purpose was to get ideas floating and explore the possibilities

of these wonderful fabrics, so that they could create their own designs

using these woven textiles. I wanted to incite the younger generation

of women to value their own dress and preserve the knowledge of weaving.”

She has already had encouraging results. “The reaction from the public

was amazing. They were inspired to see these original fabrics in a new

light and appreciate all the creative possibilities.

“I would like to go back and continue this project so that it can

have a long-term effect on the lives of the women who wear them and produce

them.”

Expanding community project

Dewan has been back to the Chittagong Hill Tracts for two summers, developing

the idea for her project. She tried to get funding from CIDA, the federal

government development agency, but “at that time the feasibility

of my project was not well developed, and my time frame was too limited

to undertake such a big project.

“I was short-listed for that grant, so I shall try again, since I

have more experience now. My fashion designer friend, Tenzing Chakma,

and I were responsible for every single detail, and we put it all together

from scratch in two months’ time. We initiated the project with our

own funds, and collected donations from various local organizations.”

She also received $500 from the Rector’s Cabinet.

“My small project became a big community project, because many people

lent their support and helped to realize it.”

Dewan is in her second year as a SIP (special individualized program)

student, combining art history, studio art and art education, and writing

her thesis on indigenous textiles in the Chittagong Hill Tracts.

She will be one of the artists featured in the show Dust on the Road:

Canadian Artists in Dialogue, presented by SAHMAT (the Safdar Hshmi

Memorial Trust), a network of Indian artists, writers, filmmakers, performers

and intellectuals who have been working in support of secularism and human

rights since 1989. The show will be on view Nov. 10 to Dec. 15 in several

venues: Dazibo, La Centrale/Gallerie Powerhouse, Oboro and Optica.

|

|

|