|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

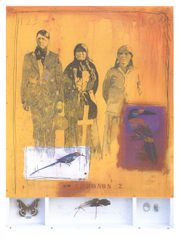

Chronos 2, 1989, by Carl Beam. Mixed media on plexiglass, 122 x 91 cm. Carl Beam is representative of the artists in Joan Reid Acland’s book. An Ojibwa from Manitoulin Island, he forged new ground in First Nations art in Canada. Acland writes, “His work is generally characterized by the juxtaposition of autobiographical, photographic, and art historical references, evoking the dissonances between Euro-American and Native cultures.” In 1986, a Beam painting was purchased by the National Gallery of Canada. It was the first Indian artwork the gallery bought since 1927. |

by Barbara Black Hot off the presses, the first book to be published by the Gail and Stephen A. Jarislowsky Institute in Canadian Art is First Nations Artists in Canada, a biographical/bibliographical guide covering the years 1960 to 1989. It’s a welcome contribution to a woefully threadbare area of scholarship, according to the author, Professor Joan Reid Acland. She has been teaching courses on contemporary native artists at Concordia for about eight years. “When I started, it was a difficult subject to access,” she recalled. “I knew a lot of these artists because of my work as an independent curator. I would just go to their studios, and watch them work and ask questions, but there were no textbooks, and few articles.” Native art went through an extraordinary period of growth starting in the 1960s. To some extent, this was given impetus by a sea change in Canadian attitudes to ethnicity. Also, official policy was changing to suit the times. The Massey Commission on the Arts (1949-51) encouraged the celebration of aboriginal art. Bans were lifted on such native practices as the potlatch, and natives got the vote in federal elections in 1961. The work itself changed, as aboriginal artists, academically trained, began to explore their own history and traditions, and to use this knowledge to make powerful statements about contemporary native life. Artists like Norval Morrisseau reclaimed ancient symbols and reworked them in exciting ways, drawing acclaim for both aesthetic and social reasons. These are the artists represented in Acland’s book. She included only those who identify themselves as aboriginal and make reference to that fact in their work. Acland also teaches her courses from a resolutely post-colonial perspective, giving her students the historical context for this work. While the art is almost always political, it is never strident. “It’s thoughtful,” she said. “Artists are researching their past.” Starting with a list of 1,000 names and whittling it down, she sent out questionnaires to about 300 of these artists, and used the information to conduct an exhaustive study of birth dates, tribal affiliation, names and dates of exhibitions, and articles about the work and the artists. She spent time in legal libraries, reading the Indian Act, since she had to investigate the political, historical and ethnographic context of the artists’ work. It was a task for which she was well suited; her PhD dissertation was an interdisciplinary project on native architect Douglas Cardinal that touched on art history, cultural studies and anthropology. A leader in native scholarship Concordia has been a pioneer in this field of scholarship, Acland said. As graduate program director in the Department of Art History, she has shepherded a number of young scholars through a field that is wide open. For example, Catherine Mattes came to Concordia from Manitoba several years ago, and has returned there. She just curated a show of leading contemporary aboriginal artists called Rielisms (a play on the name of Louis Riel, the Métis father of Confederation) at the Winnipeg Art Gallery. Caroline Stevens, a PhD, is teaching contemporary art in the Native Studies Department of Carleton University. Rhonda Meier, another graduate of Concordia’s Department of Art History, is curating an exhibit of Algonquin artist Nadia Myre. Native art continues to change dramatically, but Acland’s book is the authority on this field in this time period. It will be of great value to curators, museum directors and scholars, and Professor François-Marc Gagnon, director of the Jarislowsky Institute, is naturally proud of his first publication. Copies of First Nations Artists in Canada/Artistes des premières nations au Canada may be bought through the Concordia Bookstores, or ordered directly from Rosemary Joly, at r_joly@alcor.concordia.ca or 848-4713. An official book-launch is planned. |